Banknotes and credit notes of the Russian empire. How the Design of Russian Banknotes Changed Monetary Circulation at the Beginning of the 20th Century

Already in the middle of the 18th century, there was a need to reform the cash settlement system in tsarist Russia. The main unit of account at that time was silver and copper coins, the value of which was the universal equivalent in the country. However, the required metals were not mined as much as required, and the production cost was very high. Back in 1762, Peter III made an attempt to create a state bank that would issue paper money - banknotes up to 1000 rubles, but his project was not implemented.

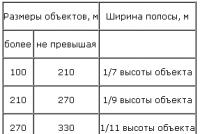

They returned to the idea of \u200b\u200bissuing paper money in 1769, when the Assignation Bank was established. Then were printed banknotes in denominations of 25, 50, 75 and 100 rubles. Their distinctive feature was the presence of a figured ornamental frame, which included not only the designation of the denomination and the place of exchange of money in Tsarist Russia, but also embossed symbols, which served as protection against counterfeiting. In addition, watermarks were additionally located along the edges, and coats of arms in the corners.

In 1818, the bills were replaced - the previous paper money circulating in the territory of Tsarist Russia was too easily forged. Now they were issued on a special, more protected material by the Expedition for the Procurement of State Papers, located in St. Petersburg. The obverse of the banknotes now adorned the Masonic crest eagle with lowered wings. In addition, the banknotes were signed personally by the cashier who issued them, and also had a facsimile signature of the manager - Prince Khovansky, different for each denomination. On the reverse side the price of the note was indicated in words. Banknotes were made of special cast paper, which was blue for 5 rubles, pink for 10, and white for higher ones. In addition, during the reform, a banknote of 200 rubles was introduced.

The catalogs of paper banknotes of tsarist Russia show approximate prices for banknotes, the cost of banknotes from the period 1769 - 1817. as a rule, it exceeds one hundred thousand rubles, sales are not rare when the auction price exceeds a million. Price for bank notes 1818 - 1843naturally a little lower, but for less than 50 thousand it is practically impossible to acquire them, even in not the best, satisfactory condition.

Another monetary reform in tsarist Russia took place in 1843, when first credit tickets, equal to the value indicated on them already to the silver coin. The front side showed the already familiar coat of arms of the Russian Empire, as well as an indication of the denomination and signatures of the persons responsible for the issue, including the director of the state bank. In addition, numbers were also applied on this part of the banknote, and for each denomination its own typeface was used. The denomination of the banknote was also duplicated in text and digital form, and on the reverse side there was an excerpt from the Tsar's manifesto on the circulation of credit notes. To protect paper money from counterfeiting, this information was typed in three different fonts in a strictly defined sequence.

In connection with the development of printing and the improvement of the quality of printing, since 1866 it was decided to issue banknotes of a higher level of security. They were created by intaglio printing using special paints and rosettes. The front side was now decorated with imperial regalia and facsimile signatures of responsible persons, and portraits of famous rulers of tsarist Russia were applied to the back side. In addition, the hallmark bills in circulation since 1866, there was a watermark with halftones.

The prices indicated in the catalogs of Russian banknotes, even for the most common credit tickets of the mid-19th century, start from 10-15 thousand. Very few bills of this period have survived, since all of them were exchanged for quite a long time without any restrictions. More details on the cost of paper money of this period can be found in specialized catalogs on bonistics.

In 1887, new paper money appearedmade using two-color printing, the decoration of which was made in the "Russian-Byzantine" decorative style. These banknotes were also distinguished by the presence of silk threads pressed into them, which increased the degree of protection. 1 and 3 ruble bills of this issue were formally valid until 1922, they remained in circulation until the first monetary reforms of the Soviet regime - however, they were gradually withdrawn as new bills were printed.

Since 1892, paper money in tsarist Russia became multicolored - during their creation, rainbow, iridescent colors, the so-called "Oryol seal" were used. Implied by the use of a single cliché to form a multi-color image. In the style of banknotes of the sample of 1892 - 1895. images of a woman were used, symbolizing great Russia in the cap of Monomakh.

During the Witte reform since 1898, the need to issue new paper money was formed. Their main difference from the old banknotes was the indication of the possibility of exchanging credit tickets for gold. In addition, the 50-ruble note was fundamentally updated, it began to be issued with a portrait of Emperor Nicholas 1, and a new 500-ruble banknote with a portrait of Peter 1 appeared.

The last bills of tsarist Russia were issued in 1905-1913. They contained intaglio printing of up to 5 colors on one side of the paper, and also differed in a completely new style, which involved the use of complex ornaments for banknotes of 3, 5 and 10 rubles. 25 rubles became portrait, with the image of Alexander 3. During the printing, banknotes with denominations of 100 and 500 rubles were subjected to some updating.

Approximate prices for banknotes of tsarist Russia of the late 19th and early 20th centuries are indicated in the articles on this site dedicated to these banknotes.

The first paper money in Russia is considered to be issued in 1769 (during the reign of Catherine II). The reasons for their appearance are quite simple: the calculation of large sums in copper coins became very difficult. For example, if you collect a hundred-ruble sum with copper coins of five kopecks, then the weight of this heap would be more than six pounds. The quality of the first banknotes was low. This paper was more likely not like a banknote, but like a receipt from a usurer.

Bank notes 1769-1843

The first Russian banknote

Bills quickly flooded the market. There was even an overabundance of them, which led to a decrease in their market value (68.5 copper kopecks per paper ruble at the end of the reign of Catherine II). Skillful hands in Russia have always been abundant. Therefore, banknotes began to be forged immediately after their appearance, as a result of which the confidence in paper money sharply decreased. Nevertheless, the experiment on the introduction of paper bank notes into the circulation of money was recognized as successful. And they protected themselves from counterfeiting by issuing new banknotes in 1786. Large denominations of 100, 50 and 25 rubles were circulated in a narrow circle of very wealthy people. But the fives and tens went to the masses, where they were immediately given the nicknames "blue" and "red". The nicknames turned out to be stable and lasted for centuries (blue is the main color of the five-ruble note and red on the ten-ruble note was even on the banknotes of the USSR from 1961 to 1991).

"Blue" and "red" sample of 1786

The appearance of fakes, however, did not stop and went on at all levels of the population. They were also painted in the villages. They were also printed by the favorites of the court in the secret rooms of palaces and estates. Napoleon also made a tangible contribution to this matter, bringing with him a lot of counterfeit banknotes. An interesting fact is that Napoleon printed signatures on bank notes, while on the originals they were put manually. Experts say that Napoleonic counterfeits are much more common than bills of official issues. For the period from 1813 to 1817, counterfeits were identified for a frightening amount of 5.6 million rubles. The result was a crushing drop in the exchange rate of paper money. The ruble on paper was exchanged for no more than twenty kopecks in coins.

"Blue" and "red" sample of 1819

At the beginning of 1818, the construction of the Expedition for the Procurement of State Papers, founded by Augustin Augustinovich Betancourt, was completed. By the fall, a batch of twenty-five rubles had already been printed. Alexander the First appointed Prince A.N. Khovansky, who took up the position and manager of the Assignation Bank. Under Khovansky, the quality of paper money issued increased significantly. It is enough to see how the paper money of 1819 and 1840 differs (the beginning and the end of the thirty-two-year reign of the prince with the works of the Expedition).

Credit Notes 1840

After the reform of silver monometallism in 1843, new credit notes appeared. The paper ruble is equated to the silver ruble with the obligatory exchange of credit cards for a precious metal or other coin. The quality of the money issued was noticeably superior to the banknotes, but the engraving work was still not at the proper height. Therefore, fakes appeared in circulation again. What are the prices for government bills of 1769-1843? Very high, as there are not very many specimens of that time.

Paper money of 1843-1896

Credit cards of the period 1843-1865

To improve the quality of paper money and protect against counterfeiting F.F. Winberg went on a business trip to Western Europe to learn from the advanced industries of that era. Upon his return, he will be appointed as the expedition manager. New is a pair of paper machines. Artistic, guilloche, electroplating and photographic workshops were established on the territory of the Expedition. Then beautiful patterns of great complexity appeared in the design, which made it much more difficult to counterfeit money.

Credit cards of the period 1863-1864

The result of the experience gained and the modernization carried out was the issuance in 1866 and 1867 of a new type of credit notes. The revolution was the presence of intaglio (metallographic) printing, watermarks using halftones, guilloche rosettes. Since 1861, the Expedition has become a commercial enterprise that has received the right to carry out private orders. The proceeds were used to extensively re-equip production areas.

Credit tickets, sample 1866

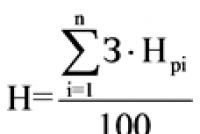

In 1881, the Expedition was connected to the power grid. A milestone event was the invention of printing a multicolor design from one cliche ("Oryol seal"). The method was developed by Ivan Ivanovich Orlov. He found himself on the Expedition almost by accident. It was planned to issue banknotes on silk fabric. Under this project, Orlov was invited from the weaving factory, where he worked as a foreman. Ivan Ivanovich designed the printing machine himself. But there is no doubt the merit of the locksmith I. Struzhkov, thanks to whom the machine became rotary. An important addition was made by the master printer A. Shcherbakov, who made it possible to add a typographic drawing with one more paint to the multicolored Oryol drawing during the same run. The multicolored prints of the Oryol seal produced banknotes that could not be counterfeited by the usual typographic method. The first in the series of bonds, printed using the new technology, were credit cards in denominations of 25 rubles (1892) and 10 rubles (1894). What are market prices state credit notes of 1843-1895? They are quite high. The specific price varies from many parameters, one of which is the demand for bonds for those who are willing to pay for it.

State credit note 1894

Paper money 1898-1917

The period of stable money circulation began with the era of gold monometallism in 1897, when, on the initiative of the Minister of Finance S.Yu. Witte carried out a monetary reform, equating the exchange rate of the ruble to gold (full gold backing of paper money). Credit notes have gained usefulness and respect from all segments of the population, taking a dominant role in money circulation, while silver and copper in the form of bargaining chips have become only an auxiliary means. How much is the paper money of tsarist Russia of this period? The price depends on the safety of the bill, on its occurrence and on the signature. For example, on a ruble dated 1898, there may be four autograph options: Pleske, Timashev, Konshin or Shipov (and the price of a ticket with Konshin's painting may exceed the cost of exactly the same ruble that Shipov signed on, five times). Why did the signatures change? Because (unlike coins) the date on the banknotes did not change. And this rule gradually became a tradition in the printing business.

Fragment of the graphic field of the credit note of 1898

The three-ruble coins were modified in 1905. For most denominations, the design changed in 1909. Large denominations changed their appearance later than anyone else (1910 for one hundred ruble denomination and 1912 for a five hundred ruble denomination). The period of prosperity ended with the entry of Russia into the First World War. Numerous issues have shaken the credibility of the paper. The final point was set by the law of June 27, 1914, which abolished the obligatory exchange of paper money for gold. Gold coins instantly disappeared from circulation. After the gold, silver hid in the egg-boxes. And paper money was printed and printed, even coming out in the form of postage stamps.

State credit note 1909

The history of printing paper money of tsarist Russia, oddly enough, was completed not by the abdicated Emperor Nicholas II, but by the Provisional Government, which continued to issue money indistinguishable from the previous design until it slipped into tiny paper squares - treasury bills of twenty and forty rubles. By October 1917, the position of paper money in Russia was deplorable. And monetary policy itself left much to be desired, as inflation equated the ruble to six or seven kopecks in pre-war purchasing power.

Fragment of the graphic field of a 1912 credit card

A small article cannot fully tell about the heyday and decline of the production of paper money in tsarist Russia. As a good guide on this topic, we recommend the book "Paper money of Russia" (authors AE Michaelis and LA Kharlamov), published for the 175th anniversary of Goznak, from which the illustrations presented here are borrowed.

The first paper money appeared in China in the 8th century. Few details of their appeal have survived, but it is known that almost immediately they provoked uncontrolled inflation. Almost a thousand years later, in the first half of the 18th century, the Englishman John Law appeared in Europe with the idea of \u200b\u200bintroducing paper money, but his proposals for a quick enrichment of the treasury were rejected by the monarchs. After a long advancement of his plan, understanding was achieved with the regent of the young French king Louis XV. A bank was established that issued interest-bearing bonds in exchange for deposits of gold and silver coins. Law took part of the proceeds for himself, the rest went to the treasury of France. Everything went well at first, until competitors started spreading rumors, which caused crowds of depositors to rush to take their money. As a result, the bank collapsed due to low coin backing. These were not quite banknotes yet, rather a financial pyramid, but in many respects the similarity with the paper money of the future was visible.

Given the enormous interest in everything French, Russia simply could not but know about all this. Nevertheless, the idea of \u200b\u200ba quick replenishment of the state budget turned out to be stronger than any prejudice. The first draft of the introduction of paper money was considered during the reign of Elizabeth Petrovna, but the Senate did not approve of the idea. Preparations for the issuance of banknotes began when Peter III ascended the throne, even draft tickets with denominations of 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 rubles were prepared. The palace coup, organized in 1762 by the wife of the emperor Catherine, put an end to all undertakings.

The next Russian-Turkish war, which began in 1768, required large expenses. Silver and gold in the treasury was sorely lacking, even a deficit of copper coins began to arise, despite the discovery of large deposits of copper ore in the Urals and Siberia. On December 29, 1768 (old style), a manifesto was issued on the establishment of exchange banks for the issue of banknotes. On February 2, the manifesto was made public. Initially, two banks were created in St. Petersburg and Moscow, and in 1772-1778, an additional 22 exchange offices were opened in other cities.

It was planned to issue tickets worth 2.5 million rubles and provide them with 2 million coins. The capital's banks received 50 thousand rubles each for expenses (paper making, printing, organization of exchange). In order to reinforce the interest of the population, 5% of bank notes were accepted as payment of taxes and fees, the rest - in coins. Unlike John Law's tickets, no interest was paid for keeping money in banknotes. In this way, they resembled bills of exchange, known long before that, but unlike them, they could act as a means of payment.

The first bank notes were in denominations of 25, 50, 75 and 100 rubles, made in a uniform style with one-sided printing. Very few copies have survived to this day, and the paint on them managed to fade and parts of the drawing are hardly visible. Each banknote has a frame, in the upper part of which there are two ovals with drawings (in the left - a port, an eagle, banners, cannons, cannonballs; in the right - a rock above the sea), at the bottom there is an inscription about the exchange of a banknote for a coin and numerous signatures of bank leaders. The denomination is indicated only in words. On the money of the Moscow Bank, “Moscow Bank” is indicated, on the St. Petersburg Bank - “St. Petersburg Bank”. The date of issue was put on the banknotes, and not the date of the sample, as it is now. The watermarks were made in the form of inscriptions: “love for the fatherland”, “acting for the benefit of the onago”, “state treasury”. That is, with all its appearance, paper money reminded of the patriotic duty of the citizens of the empire.

(from the exposition of the Goznak Museum)

Considering that the average wage the worker was 15-20 rubles a month, and the peasants mainly lived at the expense of their own economy, it becomes clear that banknotes could only be afforded by the wealthy strata of society. Because of their high value, counterfeiters immediately took up them. The most common counterfeit was the change of the word "twenty" on a 20-ruble note to "seventy", which turned it into a 75-ruble note. Since 1771, it was necessary to cancel the issue of 75 rubles and stop accepting them in all payments.

The main purpose of issuing banknotes, which was announced to the public, was to simplify the monetary circulation of the copper coin, which then occupied the bulk of all coins. The manifesto contains the following words: "the burden of a copper coin, approving its own price, burdens it and its circulation." By exchanging copper (or other) money for paper money, it was easy to transport large amounts of money, as well as store them. At first, free exchange for coins and vice versa aroused great public confidence in paper money, but the government could not resist the temptation to repeatedly continue circulations, providing them less and less.

Fall of the paper ruble and new issues

In 1786, the exchange rate of the paper ruble had already dropped by 1-2 kopecks in relation to the coin, which caused concern for the government. It is not surprising, because by this time there were already not 2, but 46 million rubles in circulation in banknotes! Of course, there were not enough coins for exchange, so payments were often delayed. Count I.I. Shuvalov proposed the following plan: to issue an additional 54 million rubles in banknotes and start issuing bail loans. At the same time, the amounts intended for issuance were clearly divided. The borrowers had to repay the full amount, including interest, after a specified period.The Moscow Bank was abolished, the issue was now carried out only by the St. Petersburg Bank (an analogue of the modern State Bank). To emphasize the importance of the actions carried out, all old banknotes were seized and new ones were issued, with additional denominations - 5 and 10 rubles on blue and red paper (hence the name of the notes “blue” and “red”). The colors of 5- and 10-ruble bills with small breaks remained until 1992.

The government assured that the volume of banknotes had reached its limit and would not be increased under any circumstances. The bank, in addition to issuing money, had to perform some other functions to replenish the state treasury. The treasury received part of the banknotes for its own needs at a small percentage, and part on a gratuitous basis. For this, the bank had the right to independently carry out the issue at its own discretion and gained some independence from the state.

By the end of the reign of Catherine II, due to constant wars, active development of the capital, enrichment of palaces, the issue of banknotes reached 150 million rubles, and their provision was only 20%. The situation was aggravated even more by the restriction of issuing coins to one person. For the paper ruble, unofficially, they now gave only 68 kopecks.

Paul I tried to rectify the situation, for this the official rate was announced - 70 kopecks, then 60 kopecks. But these innovations have not brought any significant results. The emission continued in uncontrolled volumes, and the exchange rate fell and reached 25 kopecks by the end of the first decade of the 19th century. There are known unissued banknotes of a new type in 1802-1803, apparently, it was planned to improve the economy by replacing money.

Another attempt to remedy the situation was the manifesto of Alexander I in 1810, which announced the suspension of the issue (except for the replacement of worn-out banknotes) and the mandatory redemption of banknotes in circulation. For this, a loan of 100 million rubles was organized in banknotes, the received paper money was publicly burned in front of the bank building in order to show the decrease in the mass of money and raise the confidence of the population. In the same manifesto, the silver ruble was officially recognized as the basis of monetary circulation, and copper and small silver coins became bargaining chips. Additionally, the rate of banknotes for government fees was increased, and new transactions were to be carried out only in paper money.

Napoleonic forgeries

The paper ruble, which was strengthening as a result of all the measures, was waiting for a new test, which it was no longer able to withstand. The Napoleonic army that invaded Russia in 1812 brought not only destruction, but also counterfeit money. They were prepared by a private organization commissioned by Napoleon himself. The experience of undermining the economy of the state by injecting a large number of fakes has already been mastered in Europe, moreover, this made it possible to supply the army with food on foreign territory.Bags with fake banknotes (only 25 and 50 rubles are known) were carried along with all the equipment, and along the way were used for calculations in the villages. The peasants were reluctant to accept money from the French, but generally did not refuse, since purchases were made at high prices. No one would have thought that the great emperor would condescend to issue counterfeit money. But soon the shortcomings of bills began to come to light, which were clearly traced among certain dates. First, the corners were trimmed much smoother than the real ones, and some copies even had grammatical errors.

Nowadays collectors know four types of counterfeit banknotes: with the word “weeping coin” instead of “walking coin”; with the word "state" instead of "state"; with two errors; and also without errors. The latter differs only in the technology of cutting corners.

Recent attempts to restore the hardness of the paper ruble

The mass production of counterfeits greatly undermined the already shaky confidence in paper money, the exchange rate reached 20 kopecks. By 1817 there were already 836 million rubles in banknotes in circulation. Since this year, several more government bank notes are being organized. Some loans are made in interest, and some are taken immediately with a premium to the amount. This all reduced the money supply, but the exchange rate rose by only 5 kopecks.

(from the exposition of the Goznak Museum)

To get rid of counterfeits, in 1819, another exchange of all banknotes for new ones was made, and the old ones were invalidated and were not accepted for payments. New money began to have more complex designbut remained one-sided. Additionally, a banknote of 200 rubles was introduced. It was planned to issue a par value of 20 rubles, but it remained in a trial version.

(from the exposition of the Goznak Museum)

Finance Minister E.F. Kankrin in 1839 abolishes the exchange of paper money for coin. The issue of interest on deposits is carried out only in banknotes, which now have a strict rate of 30 kopecks in silver, and the issue of coins to one person is limited to 100 rubles. For this purpose, special copper coins were issued with the designation in "kopecks in silver", having a large size. Acceptance of banknotes in government payments is terminated.

Credit tickets

The reform of E.F. Kankrina. Silver standard

Various ideas were put forward to improve the economy. Emperor Nicholas I proposed introducing tickets, according to which depositors could receive a profit as a percentage, but this was already carried out in the second decade of the 19th century and led to negative consequences. Instead of increasing silver in the treasury, state debt... Therefore, the reform organized by E.F. Kankrin in 1839-1843 meant the introduction of new paper money, and not government loans. The savings banks established in 1842 (predecessors of the modern Sberbank) were engaged in loans at interest.The first stage of the reform consisted in the formation of a bargaining chip in a silver coin. For this purpose, they organized a deposit box office and from January 1, 1840 issued deposit tickets in denominations of 3 to 25 rubles, which a year later were replenished with 1, 50 and 100 rubles. Deposits were accepted in silver and gold coins and were freely given out to depositors without limiting the amount. There were so many people willing to invest that there were queues at the exchange offices. During the first year, they managed to collect 24 million rubles in coins.

Deposit tickets were completely identical to the first banknotes, but were supported by stable reserves of coins in the treasury. The silver ruble has been the basis of monetary circulation for 20 years, and in order to use copper, large copper coins are issued with the designation in "silver kopecks". In this way, the government managed to completely equate all three types of coins - gold, silver and copper, but the calculations were still carried out in silver.

(from the exposition of the Goznak Museum)

The summer of 1841 brought little harvest to the country, it was necessary to start purchasing abroad, so the inviolable exchange fund began to gradually melt. At the end of the year, a Loan Bank was organized, which issued credit tickets with a face value of 50 rubles, partially backed by silver. Tickets were issued mainly against real estate security, but there was also a direct exchange for silver.

From June 1, 1843, the last stage of the reform was carried out: all existing paper money was exchanged for new credit notes of the 1843 model with denominations of 1, 3, 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 rubles. The exchange was made 1: 1 for deposit tickets and tickets of the Loan Bank, and for bank notes at the rate of 3 rubles 50 kopecks per new ruble. Credit tickets were obligatory backed by silver and gold coins for at least 1/3. Since 1860, the creation of the State Bank, which replaced the Commercial Bank, took over the issue of bank notes.

Simple exchange without any restrictions helped to increase public confidence in credit notes, they were freely circulated and willingly accepted in all payments. The exchange fund was sufficient with a margin, and the surplus went to state needs... Due to the economic crisis in other European countries, many foreigners came to Russia to exchange their savings for hard credit notes.

In terms of their decoration, the credit notes were similar to the banknotes of the latest issues: a figured frame with an indication of the denomination, inside which information about the required amount for a gold or silver coin, and the signatures of officials. On the back, against the background of the state emblem, there were excerpts from the Imperial Manifesto on credit notes.

Credit cards in the second half of the 19th century

For 10 years, credit tickets remained a solid form of money, and because of their convenient use, they were in great demand among the population. But, like any paper money, sooner or later depreciation awaited them. The reason was the uncontrolled emission to cover government spending during the Crimean War. By 1858, the paper ruble was already worth 80 kopecks. This further provoked queues at the change offices, and therefore reduced confidence in credit tickets.

(from the exposition of the Goznak Museum)

If earlier silver and gold were accumulated by the population, and in order to normalize monetary circulation, it remained only to find a way to extract it (for example, with the help of loans). Now the precious metals went abroad, the population bought more stable British pounds. It was possible to partially eliminate the shortage of the silver coin by lowering the weight, and then the samples of 5, 10, 15 and 20 kopecks from silver. The coins became smaller and contained only less than half of the precious metal. The issuance of coins to one person was also limited - no more than three rubles, the rest had to be issued in credit tickets.

Improvements in the 1860s financial system allowed to raise the exchange rate of the paper ruble, but the next Russo-Turkish war again forced to resort to the mass printing of bank notes, which quickly reduced their cost to an average of 66 kopecks.

In 1881, with the coming to power of Alexander III, previously printed credit notes with a denomination of 25 rubles on the model of one-sided British pounds came into circulation. Public confidence in the pounds should have gone to these tickets, but the experiment did not show significant results. Trying to deal with the huge paper money accumulated among the population, the emperor signed a decree to stop issuing credit notes, which already had more than a billion rubles. The decree assumed an annual reduction in paper money by 50 million, but in 10 years it was possible to withdraw tickets only by about 150 million rubles.

The appearance of the banknotes did not remain unchanged. In 1866, new banknotes of the same denominations appeared, but for the first time in history portraits of Russian rulers appeared on large ones. On 5 rubles - Dmitry Donskoy, on 10 - Mikhail Fedorovich, on 25 - Alexey Mikhailovich, on 50 - Peter I, and on 100 rubles - Catherine II. Why the artist chose them, and by what principle the portraits were selected for each denomination, is unknown. Already at the end of the 1880s, new tickets were issued in denominations of 1 to 25 rubles, already without portraits, and 50 rubles were no longer printed. The longest lasted 100 rubles, issued unchanged until 1896, they had a rainbow background, which was then the pinnacle of the printing art. The portrait of Catherine II on a 100-ruble note will survive the subsequent reform (with a change in the design of the banknote), will last until the Revolution, and will be called so - "katenka".

Tickets of the same design could be issued under different rulers, while only the emperor's monogram was changed. For example, 100 rubles were with the monogram of Alexander II, Alexander III and Nicholas II. Until 1898, the date of issue was put on the money, after which they began to designate the date of the sample. In the 1890s, pre-reform tickets in denominations of 5, 10 and 25 rubles were renewed for the last time, they received a complex highly artistic design in the spirit of the imperial time.

The reform of S.Yu. Witte. gold standard

At the beginning of the reign of Nicholas II, the Minister of Finance was a competent politician and economist Sergei Yulievich Witte. Back in 1895, he proposed to transfer the Russian monetary system to the gold standard, that is, each ruble would be expressed in a certain amount of gold, and silver and copper coins would become bargaining chips. Due to the clear peg to gold, the depreciation of money was theoretically impossible.It was necessary to gently, without unnecessary shocks, equate the new ruble to 1.5 old ones (at the established rate). And there were enough shocks at that time: growing distrust of the authorities, strikes and revolutionary movements, terrorism.

The largest gold coin the denomination of 10 rubles was then unofficially called the imperial. New coins of the same weight were developed, denominated not only in rubles, but also in imperials: “IMPERIAL. 10 RUBLES GOLD ", was also a semi-imperial. At the same time, attempts were made to name the largest coin “Rus” or “Rus”. All this did not go beyond the trial copies. Instead of new money, they decided to simply exchange the old 10 rubles for new 15, for this purpose, in 1897, coins with a denomination of 15 and 7.5 rubles were issued in mass circulation, weighing 10 and 5 old rubles, respectively. And the new 10 rubles reduced the weight by one and a half times, and they were equated to 10 new "gold" paper rubles.

But in order to introduce a new type of credit notes, a significant exchange fund in gold coins was needed. Until that time, little attention was paid to gold, it was not in great demand. To create a reserve fund, even 20 years before the reform, decrees began to be issued on the preferable acceptance of the gold coin in government payments and as duties, as well as foreign currency in gold terms. Additionally, deposits are introduced, accepted in gold in exchange for deposit receipts.

Since 1895, many government fees are expressed in gold and are calculated daily at the rate of metal reception. The silver ruble became equal to 17.424 shares of pure gold, that is, to 0.774 grams. This was exactly 2/3 of the weight of the old-style gold ruble. Old-style paper money is accepted at the rate of 15:10. That is, the population gradually mastered settlements in gold bars, the paper form of which was to become credit notes.

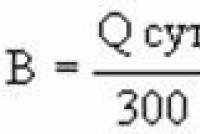

New credit notes were issued in 1898. The denominations of 1, 3, 5, 10 and 25 rubles remained the same design, but instead of indicating the obligatory exchange for a silver coin, an inscription appeared on them about the exchange of each ruble for 17.424 shares of pure gold, or 1/15 of the imperial. The name "imperial" is transferred to a 15-ruble coin. Completely new banknotes of 50, 100 and 500 rubles with portraits of Nicholas I, Catherine II and Peter I, respectively. Old gold coins were not seized and were equated to 1.5 new ones. Silver and copper coins did not change their appearance and weight, but became a secondary means of payment. Issuance of credit notes was limited to at least 50% of the gold coin backing, and the issue of over 600 million was to be fully backed by gold.

Among influential circles, there were many opponents of the reform, who believed that Russia was not ready for the transition to the gold standard, in contrast to the more developed countries. The prosperous existence of a monetary system of this type was possible only if there was a large gold reserve, and in the event of the slightest shock, it would go abroad. And so it happened, the strong ruble lasted only 16 years.

Currency circulation at the beginning of the 20th century

Russia entered the new century with stable paper money backed by a large gold reserve. Even the Russo-Japanese War had only a marginal impact on emissions. Instead of issuing all credit notes, the government focused on printing low denomination tickets. At the same time, 3 rubles of a new model appeared, which were printed in the first months of the Soviet era.Under Nicholas II, many transformations were aimed at the flourishing of the autocracy, despite the growth in the number of revolutionary movements. The changes have not spared money either. In 1909-1912, banknotes of a new design from 5 to 500 rubles were issued, made with excesses of decoration in the spirit of the Baroque. On them, in richly decorated figured frames, there were portraits of Russian emperors, there were images of complex architectural elements, a multicolored background, and microtext. Particularly noteworthy is the 500 rubles sample of 1912 with a portrait of Peter I and a full-length female figure, symbolizing Russia. Only 50 rubles, a ruble and 3 rubles were left unchanged.

Money circulation reached unprecedented heights, and it seemed that nothing threatened him anymore. To confirm this, it is worth citing a few numbers. At the beginning of 1914, there were about 2.5 billion rubles in circulation in banknotes and coins of all types. Of these, 1,664 million rubles were in credit notes, 494.2 million in gold coins, 226 million in silver and 18 million in copper coins. At the same time, the gold reserves of the State Bank overlapped credit notes for 31 million rubles. That is, according to the 1898 manifesto, it was allowed to issue more than 300 million rubles in paper money without increasing the exchange fund.

After Russia entered the First World War in 1914, uncontrolled emissions began. In just three years, the number of banknotes rose to 10 billion rubles, and the exchange rate of the paper ruble became fluctuating again. At the beginning of 1917, only 25 kopecks were given for it, and in Europe it was quoted at the rate of 0.56 to a gold coin. Silver and gold began to settle among the population, the issue of the coin stopped.

In 1915, instead of silver coins, money-stamps in denominations of 10, 15 and 20 kopecks appeared in circulation, made on the model of postage stamps for the 300th anniversary of the Romanovs. They were produced in sheets of 100 with tear-off perforations. On the front side there were portraits of emperors, on the back side there was a coat of arms and face value in numbers and words. At the same time, the copper coin is gradually being replaced by banknotes-cards in denominations of 1, 2, 3 and 5 kopecks, and a note of 50 kopecks also appears. 10, 15 and 20 kopecks of this type did not go into circulation and are now considered rare. IN next year money-stamps come out in denominations of 1, 2 and 3 kopecks. Copper coins were completely minted in 1917, and silver ones in 1916. Gold coins have not been produced since 1911.

Money of the Provisional Government

After the February Revolution, representatives of the former State Duma and other politicians who formed the Provisional Government. To begin the reforms that the opponents of the tsarist government were waiting for, it was necessary to increase the issue of paper money. For 8 months, 9.5 billion rubles were printed in credit notes.Banknotes have been issued unchanged for many years, the only differences were in the signatures of the manager and cashier, as well as in the series of numbers. By comparing all these parameters, collectors can determine the exact year of printing, since all of them bear only the date of the sample. For example, the ruble with the date "1898" was signed by the manager of Pleske, who was at the helm of the State Bank until 1903, then Timashev took his place, and in 1910 Konshin. Among the rubles with the signature “I. Shipov ”there are four main types: 1914-1916, 6 digits in the number; 1916, 3 digits in the number; issue of the provisional government and release of the Soviet government. There were also local issues of the Arkhangelsk province with perforation "GBSO", they exist with different numbers and signatures. A novice collector picks up a bill with the date "1898" and does not even suspect that it was issued already under Soviet rule, although there are most of these banknotes.

In addition to the tsarist banknotes, in the summer of 1917, the issuance of completely new banknotes of 1000 rubles with the coat of arms of the Provisional Government began: a two-headed eagle without crowns (similar to the modern emblem of the Central Bank). On the front side of this money there was an image of the building of the State Duma, for which they were nicknamed "Dumka" or "Duma money". In the fall, by decree of the chairman of the government, Kerensky, small cards with a face value of 20 and 40 rubles are issued in uncut sheets of 40, they immediately received the nickname "kerenki". Also in September, the issue of banknotes with a denomination of 250 rubles began. Some are horrified to discover a swastika on the banknotes of the Provisional Government, which is not noticeable upon a cursory examination. In fact, this symbol had not yet been taken by the fascists and meant a peaceful existence, but it appeared long before that in India.

Under the Provisional Government, instead of a bargaining chip, they continued to issue money-marks with denominations of 1, 2 and 3 kopecks. They were distinguished by the presence of a black overprint in the form of a denomination number on the front side. Under Soviet rule, at first, these denominations were also printed, but on the reverse side, instead of the coat of arms, the denomination was repeated in black paint.

1. Gusakov A.D. "Currency circulation of pre-revolutionary Russia". - M., 1954.2. Gusakov A.D. "Essays on the money circulation in Russia". - M .: Gosfinizdat, 1946.

3. Shchelokov A.A. "Paper money. Historical facts, legends, discoveries".

Photos provided by site users: Shurik92, Letta, Kuzbass, Admin, MushrO_Om

Today, the site recalls and shows the evolution of Russian banknotes, starting with the era of Catherine II and ending with a limited series of banknotes of the new Russia in honor of the Sochi 2014 Olympic Games.

The first paper money of the Russian Empire

The first paper money in the Russian Empire was the denominations of 25, 50, 75 and 100 rubles, issued in 1769.

They were printed on white watermarked paper. Then it was the peak of technology.

The new Russian money was called bank notes and was printed in two banks established by the Empress Catherine II in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

The official goal of replacing copper money with paper money is the need to reduce the cost of issuing money, although they say that in fact in this way the wise empress raised funds to organize the Russian-Turkish war.

State credit notes 1843-1865

The introduction of new technology in the State Papers Procurement Expedition made it possible to improve the appearance of tickets and strengthen their protection.

Everything is done in traditional colors: 1 rub. - yellow, 3 rubles. - green, 5 rubles. - blue, 10 rubles. - red, 25 rubles. - purple, 50 rubles. - gray and 100 rubles. - brown. The face copy with the number and coat of arms of Russia is made in black paint.

On the reverse side, the text is in black paint, and on tickets worth 100 rubles. underlay grid color - rainbow printing (iris). This was done for the first time. Subsequently, iris was used very often on nets.

"Petenka"

The largest denomination of the Russian Empire is the 500 ruble denomination, issued from 1898 to 1912.

500-ruble banknote

The size of the bill is 27.5 cm by 12.6 cm. In 1910, one “petenka” is two annual salaries of the average Russian worker.

Kerenki

The banknotes that were issued by the Provisional Government in Russia in 1917, and in the period from 1917 to 1919 the State Bank of the RSFSR on the same clichés before the appearance of Soviet banknotes, were called "kerenki", after the last chairman of the Provisional Government A.F. Kerensky.

As banknotes, they were valued very low, and the people preferred tsarist money or banknotes of the government, which at that time seized power in a particular territory.

Small kernels (20 and 40 rubles) were supplied on large uncut sheets without perforation, and they were simply cut off from the sheet at the time of payment of wages. A sheet of 50 kernels with a total denomination of 1000 rubles was popularly called "piece". They were printed in different colors, on unsuitable paper, and sometimes on the back of product and product labels.

250 rubles bill 1917 Year of release

Limbard

One billion rubles bill

In the early 1920s, during the period of hyperinflation in the Transcaucasian Soviet Socialist Republic (and these are the Azerbaijan, Armenian and Georgian SSRs), a banknote with a face value of 1 billion rubles was issued (colloquially - limard, lemonard).

One billion rubles bill

On the front side of the banknote, the denomination was depicted in numbers and letters and contained warning inscriptions, and on the back side, the artists depicted a woman worker, the coat of arms of the ZSFSR and floral ornaments.

Paper chervonets

After 1917, the banknote of 25 Soviet chervonets became the largest in terms of purchasing power.

It was backed by 193.56 grams of pure gold. It should be noted that at the same time as the paper ducat issued in the fall of 1922, the Soviets began to issue gold ducats in the form of 900-proof coins.

In size, the Soviet chervonets fully corresponded to the pre-revolutionary 10 rubles coin.

Payment checks of Natursoyuz

In 1921, during the rampant hyperinflation of Soviet rubles and famine, the Kiev Natursoyuz issued settlement checks in denominations of 1 pood of bread. Natural checks were issued in denominations of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 natural rubles or poods.

It was reported that "the smallest denomination of a naturche of the Union is equal to 1 naturkopeck, which is 1/100 pood of rye flour, 10 naturkopiek is 1 share, and 100 naturkopiek is 1 natural ruble (pood of rye flour)"

1947 monetary reform

A ticket in denomination of 1 rub. printed on the front side by a typographic method in two colors, and on the back side by an Orlov method in five colors, including iris.

1961 USSR bank tickets

Tickets in denominations of 10 and 25 rubles. printed on the front side by intaglio printing on a two-color typographic grid, and on the back side - typographic printing on the Oryol five-color substrate grid. All bank notes have two six-digit numbers. Paper with a common watermark.

Tickets are worth 100 rubles. are similar to tickets for 50 rubles, but the Oryol net is on the front side. Intaglio printing on the front and back sides.

Vneshtorgbank checks of the USSR

In the USSR, there was a chain of stores "Berezka", where they accepted checks of the "D" series.

These checks were pecuniary obligation The State Bank (Vneshtorgbank) of the USSR on the payment of the amount specified in the check and were intended for settlements of certain categories of citizens for goods and services. All receipts were printed at GOZNAK.

Coupons for scarce goods. USSR

In the early 1990s, the country of the Soviets was struck by a massive deficit, and money alone became insufficient to purchase goods.

The Soviet bureaucracy remembered the tried-and-true method of distributing scarce products by cards, but at the same time used the delicate word “coupons”.

Tickets of the State Bank of the USSR, sample 1991−92

When the collapse of the USSR began (1991-1995), the ruble was gradually withdrawn from circulation. The last country to abandon currency on May 10, 1995 was Tajikistan.

Bank of Russia ticket samples 1995

Bank of Russia tickets 1995

The designer who developed the design for most of the Soviet banknotes was the engraver and artist Ivan Ivanovich Dubasov.

1997 Bank of Russia tickets

100 rubles, sample of 1997

500 rubles, sample of 1997

Vertical banknote

100-ruble banknote issued for the 2014 Olympics

For the 2014 Olympics, the Bank of Russia issued a commemorative banknote of 100 rubles. The total circulation of the banknote is 20 million copies. This is the first Russian vertically oriented banknote.

On December 29, 1768, Catherine II signed a manifesto on the introduction of banknotes in Russia - this is how the first paper money appeared in Russia. In St. Petersburg and Moscow, branches of the Assignation Bank were established, which received the exclusive right to issue banknotes. The manifesto said that banknotes were in circulation on a par with a coin and were subject to immediate exchange for coins on demand in any quantity.

The appearance of banknotes was caused by large government spending on military needs, which led to a shortage of silver in the treasury (since all payments, especially with foreign suppliers, were carried out exclusively in silver and gold coins). The shortage of silver and the huge mass of copper money in the domestic Russian trade turnover led to the fact that large payments were extremely difficult to make. So the county treasuries were forced to equip entire expeditions when collecting poll taxes, since a separate supply was required to transport an average of every 500 rubles of tax. All this made it necessary to introduce a kind of bills of exchange for large settlements.

From January 1, 1769, bank notes of four denominations began to be issued: 25, 50, 75 and 100 rubles. They were printed in black ink on white watermarked paper. The money of this issue had a primitive appearance, which made it easier to falsify. The size of the notes was 190 x 250 mm. In the photo: 25 rubles 1769.

The second type of banknotes began to be issued in 1786. Colored paper made at a special manufactory in Tsarskoe Selo began to be used for printing. In everyday life, paper money was often named by color. In the photo: a note with a denomination of 5 rubles or "blue" in 1794. 173 x 134 mm.

In 1802-1803, new banknotes in denominations of 5, 10, 25 and 100 rubles were prepared, but they never went into circulation. Banknotes of this type are known only in samples. The number 515001 is the same on all banknotes. The sizes of banknotes of each denomination are not the same.

On January 1, 1820, the exchange of old 5 and 10-ruble notes for new ones began. The color of the paper remains the same, but the drawing has undergone significant changes. Bank notes of this type were issued and were in circulation until 1843. In the photo: 5 rubles 1821.180 x 132 mm.

In 1840, as a result of the monetary reform of the Minister of Finance Kankrin, the banknote ruble was abolished. Copper coins, tied earlier to the banknote ruble, again received a rigid exchange rate with silver, and the silver ruble itself in the form of a coin was supplemented with deposit notes, and since 1843 with credit notes. In the photo: 10 rubles 1840.145 x 100 mm.

50 rubles 1841

10 rubles 1854 115 x 160 mm

In 1869, a new type of credit notes (model 1866) were introduced into circulation. The denominations of 5, 10, 25, 50 and 100 rubles contained portraits of Russian rulers, which marked the beginning of the tradition of depicting statesmen on money. In the photo: a note of 100 rubles 1872.180 x 102 mm.

10 rubles, state credit note of 1882.

10 rubles 1894 104 x 174 mm.

In 1895-1898, under the leadership of Sergei Witte, a monetary reform was carried out, during which the gold ruble became the basis of circulation, which included 17.424 shares of pure gold (about 0.77 grams). Gold coins were free to circulate along with paper notes of credit. In the photo: 1 ruble state credit note, 1898. 142 x 83 mm.

100 rubles of issue of 1898. The traditional color of the banknote is yellow-beige, pastel shades. Because of the depicted Catherine II, the banknote was nicknamed by the people "katenka". 260 x 122 mm.

Banknote of 50 rubles, sample of 1899. Nicholas the First is depicted on the obverse. 188 x 118 mm.

Banknote "petenka" of 500 rubles, sample of 1912. Obverse with the image of Emperor Peter the Great. For the first time in the history of Russia, a banknote of such a large denomination was developed in 1897, and in 1898 it was put into circulation. The size of the bill is larger than A4, 275 x 128 mm.